I am constant as the northern star,

Of whose true-fix’d and resting quality

There is no fellow in the firmament.

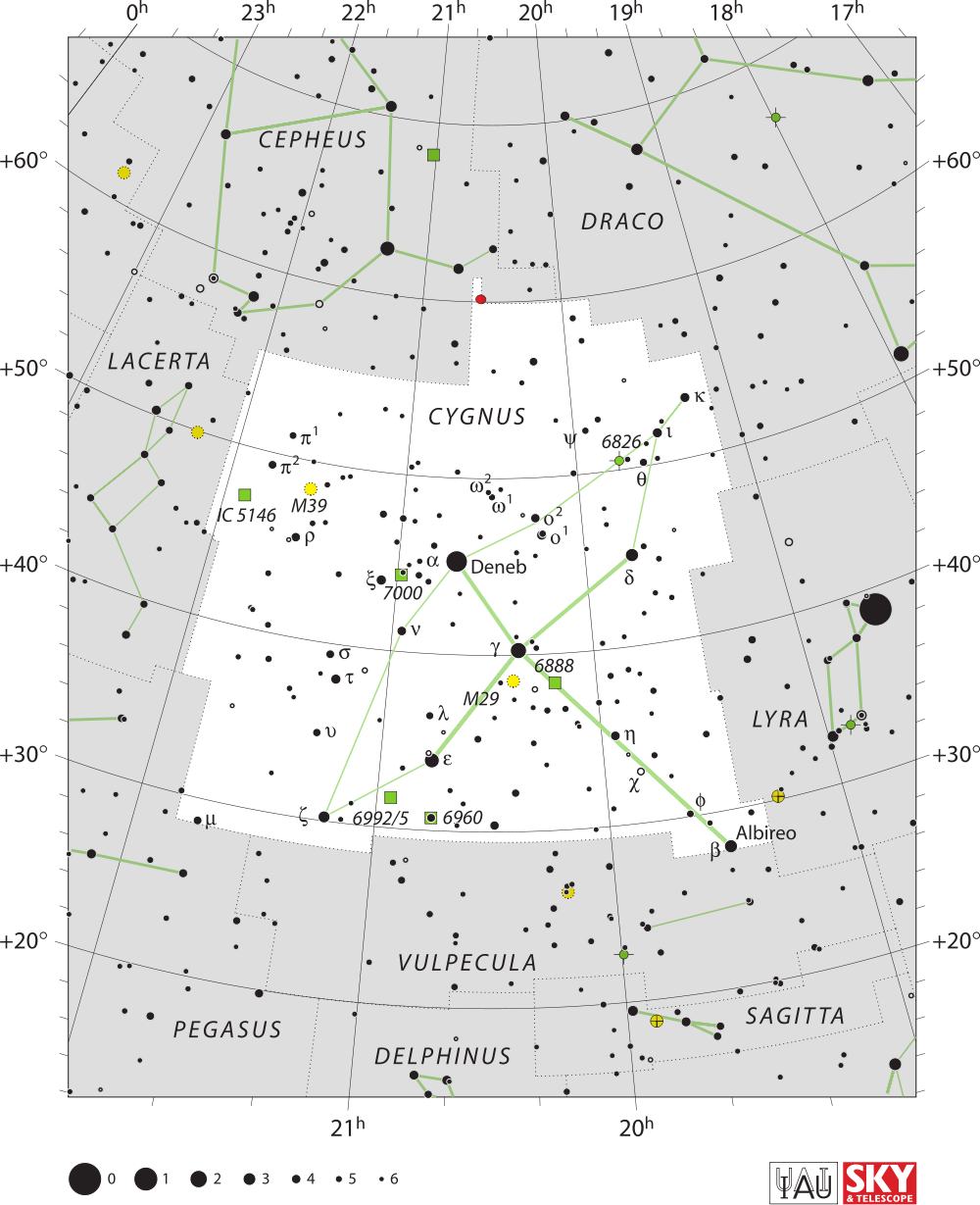

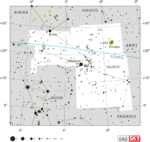

May is the third month of Leo Term in the River Houses, and as our monthly star calendar will tell you, May’s Great Star is Polaris, the Pole Star in the constellation Ursa Minor, the Little Bear (which includes the asterism called the Little Dipper). Its formal designation is α Ursae Minoris — “alpha of Ursa Minor.” If you live in the northern hemisphere, Ursa Minor, the Little Dipper, and Polaris are up in the night sky all year long, marking the location of the celestial pole, the point directly above earth’s north pole. The angular elevation of Polaris above the horizon corresponds to your latitude, so if you’re standing at the north pole, Polaris is directly overhead (90° up from the horizon) and your latitude is as high as it can go: 90°N.

![[Polar Star Trails]](https://riverhouses.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/polaris-star-trails.jpg)

If you want to introduce your students to Ursa Minor and Polaris you can start with some basic astronomy and astronomical mythology from your backyard star guide:

This northernmost constellation is visible year-round to star-watchers in the Northern Hemisphere. Its value as a navigational tool was recognized long ago, and travelers still look to the Little Dipper to locate Polaris. Other stars in the sky rotate around the celestial pole, making Polaris and the Little Dipper reliable constants in the night sky not only for travelers but also for those navigating the stars. Earlier cultures even used it as a clock, marking time as the constellation swung around the seemingly fixed point of the North Star. (Backyard Guide to the Night Sky, page 198)

That’s plenty for beginning students — your little lesson is done. If you want to get more advanced, the Wikipedia page on Polaris is packed with additional information on everything from astrometry to cultural history.

![[Ursa Minor Chart]](https://riverhouses.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/polaris-ursa-minor-chart.png)

The Polaris we see as a single star is in fact a triple star system. The primary star of the system — the source of nearly all the light that comes to us — is a yellow supergiant (Polaris Aa) more than 30 times the diameter of the sun. It has a tiny close companion (Polaris Ab) that can only be detected in powerful telescopes, and a more distant companion (Polaris B) that can be fairly easily resolved by amateur observers. The Polaris system is about 400 light-years distant: the light we see when we look at Polaris was actually emitted by the star about 400 years ago.

![[How to Find Polaris]](https://riverhouses.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/polaris-ursa-major-ursa-minor.jpg)

One of the easiest ways to locate Polaris is to find the Big Dipper (which is more conspicuous in the sky than the fainter Little Dipper), and then trace along from the two “pointer stars” to Polaris. Once you’ve located Polaris in the familiar surroundings of your neighborhood or backyard (“just above and to the left of the red maple tree”) you’ll never need search for it again, because unlike the seasonal stars that cross the sky through the night, Polaris will always be in the same place, winter and summer, spring and fall. (“I am as constant as the northern star,” says Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar.)

![[Ursa Minor]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3f/Sidney_Hall_-_Urania%27s_Mirror_-_Draco_and_Ursa_Minor.jpg/719px-Sidney_Hall_-_Urania%27s_Mirror_-_Draco_and_Ursa_Minor.jpg)

Sometime this month, take your homeschool students out after dark and introduce them to this great celestial sky-mark, and teach them its name, and so give them a new friend for life.

What astronomical observations and stellar sightings have you and your students made in your homeschool this Leo Term? 😊

❡ Alpha and beta and gamma, oh my: Most of the principal stars within each constellation have both old vernacular names — Vega, Sirius, Arcturus, and so on — as well as more formal scientific designations. The German astronomer Johann Bayer (1572–1625) devised the formal system of star designations that is still in common use today. In Bayer’s system, the stars in each constellation, from brightest to dimmest, are assigned a lowercase letter of the Greek alphabet: α (alpha, brightest), β (beta, second brightest), γ (gamma, third brightest), δ (delta, fourth brightest), and so on. This letter designation is combined with the name of the constellation in its Latin possessive (genitive) form: Lyra becomes Lyrae (“of Lyra”), Canis Major becomes Canis Majoris (“of Canis Major”), and so on. The brightest star in the constellation Lyra (the star Vega) thus becomes α Lyrae (“alpha of Lyra”), the brightest star in Canis Major (the star Sirius) becomes α Canis Majoris (“alpha of Canis Major”), and so on, through all 24 Greek letters and all 88 constellations. How bright would you expect, say, the σ (sigma) star of Orion to be? Not very bright — it’s far down the alphabet — but σ Orionis happens to mark the top of Orion’s sword, so even though it’s not very bright it’s still notable and easy to locate on a dark night. ✨

❡ Star bright: The brightness of a star as we see it in our night sky is its magnitude — or more properly, its apparent magnitude. The scale of star magnitudes was developed long before modern measuring instruments were invented, so it can be a little bit confusing for beginners. Originally, the brightest stars in the sky were called “first magnitude” and the less-bright stars “second magnitude,” “third magnitude,” and so on, down to the dimmest stars visible to the naked eye, which were called “sixth magnitude.” In the nineteenth century the star Vega (our August star) was chosen as the standard brightness reference and its value on the magnitude scale was defined to be zero (0.0). Five steps in magnitude (from 0.0 to 5.0 or from 1.0 to 6.0) was defined to be a change in brightness of 100 times: a star 100 times dimmer than Vega (0.0) was defined to be a magnitude 5.0 star. Vega is not quite the brightest star is the sky, however, so the scale also had to be extended into negative numbers: Sirius (our March star), for example, is magnitude –1.5, about three times brighter than Vega (at 0.0). The planet Venus at its brightest is about magnitude –4.2; the full moon is about magnitude –12.9; the sun is magnitude –26.7. By contrast, the dimmest stars visible to the naked eye in a populated, light-polluted area are about magnitude 3.0; the dimmest stars visible under very dark conditions are about magnitude 6.5. The Hubble Space Telescope in orbit around the earth has photographed distant stars and galaxies below magnitude 30, the dimmest celestial objects humans have "seen" so far. 🌃

❡ And all dishevelled wandering stars: How far away are the stars? To answer that question we have to begin with one of the most basic phenomena of astronomy: the distinction between the planets (“wanderers”) and the fixed stars. The fixed stars form the constellations, and they all move in concert, rotating through the sky every night around the celestial pole. The planets, by contrast, move among the fixed stars week by week, following a regular narrow track called the ecliptic. The Big Dipper is always the Big Dipper, but Jupiter will be in one constellation this month, and then another next month, and then another the month after that. (The constellations that the planets pass through along the ecliptic comprise the zodiac.) The wandering planets seem obviously nearer to us than the fixed stars and they move at different speeds, but are the fixed stars themselves all the same distance away? Do they all occupy a single celestial “dome” that rotates through the heavens (as some ancient and medieval astronomers believed), or are they scattered through space at different individual distances? Astronomers had long suspected that the fixed stars existed at different distances from us, but early attempts to measure those distances failed. It was not until the early 1800s that instruments and measuring techniques became precise enough to allow the first stellar distances to be calculated through the study of parallax. Parallax is the displacement in the apparent position of an object with respect to the background when an observer moves from side to side. It’s an ordinary phenomenon you experience every day — it’s how we judge distances as we move through the landscape. Stellar parallaxes are extremely small — fractions of an arc-second (one 3600th of a degree) — and they are calculated by measuring a star’s position against the background at opposite sides of the earth’s orbit, six months apart. (That’s the astronomical equivalent of taking one step to the side.) Vega, our August star, was one of the first stars to have its parallax measured; modern estimates put it at about 0.13 arc-seconds. Apply some trigonometry, and that yields a distance of about 25 light-years. 🔭

❡ Watchers of the skies: Teaching your homeschool students to recognize the constellations is one of the simplest and most enduring gifts you can give them. We recommend the handy Backyard Guide to the Night Sky as a general family reference — it will help you identify all the northern hemisphere constellations and will point out many highlights, including the names and characteristics of the brightest stars. Your recommended world atlas also has beautiful maps of the whole northern and southern hemisphere night skies on plates 121–122 (10th and 11th eds.). Why not find a dark-sky spot near you this month and spend some quality homeschool time beneath the starry vault. 🌌

❡ Hitch your wagon to a star: This is one of our regular Homeschool Astronomy posts featuring twelve of the most notable stars of the northern hemisphere night sky. Download and print your own copy of our River Houses Star Calendar and follow along with us as we visit a different Great Star each month — and make each one of them a homeschool friend for life. 🌟

❡ Print this little lesson: Down at the bottom of this post you’ll find a special “Print” button that will let you create a neat and easy-to-read copy of this little lesson, and it will even let you edit and delete sections you don't want or need (such as individual images or footnotes). Give it a try today! 🖨

❡ Homeschool calendars: We have a whole collection of free, printable, educational homeschool calendars and planners available on our main River Houses calendar page. They will help you create a light and easy structure for your homeschool year. Give them a try today! 🗓

❡ Support our work: If you enjoy our educational materials, please support us by starting your regular Amazon shopping from our very own homeschool teaching supplies page. When you click through from our page, any purchase you make earns us a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thank you for helping us to keep going and growing! 🛒

❡ Join us! The aim of the River Houses project is to create a network of friendly local homeschool support groups — local chapters that we call “Houses.” Our first at-large chapter, Headwaters House, is now forming and is open to homeschoolers everywhere. Find out how to become one of our founding members on the Headwaters House membership page. 🏡