➤ Special note: The Great Backyard Bird Count is coming up on Washington’s Birthday weekend (14–17 February 2025) all across the country and around the world! It’s one of the best homeschool science activities you can participate in all year. How many birds will you find in your neighborhood? 🐦

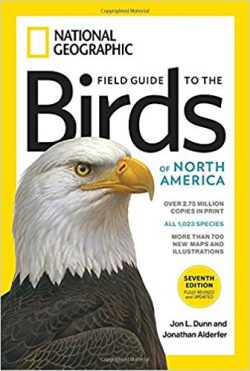

Every Friday we invite you and your homeschool students to learn about a different group of North American birds in your recommended bird guide. It’s a great way to add a few minutes of science, geography, natural history, and imagination to your homeschool schedule throughout the year.

This week’s birds (two different families) are the Barn Owls (pages 294–295) and the Typical Owls (pages 294–303).

If you’re teaching younger children, the way to use these posts is just to treat your bird guide as a picture book and spend a few minutes each week looking at all the interesting birds they may see one day. With that, your little lesson is done.

If you have older students, one of your objectives should be to help them become fluent with a specialized reference book that’s packed with information, the kind of book they will encounter in many different fields of study. Here’s how your bird guide introduces this week’s birds:

BARN OWLS and TYPICAL OWLS — Families Tytonidae and Strigidae. Distinctive birds of prey, divided by structural differences into two families, Barn Owls (Tytonidae) and Typical Owls (Strigidae). All have immobile eyes in large heads. Fluffy plumage makes their flight nearly soundless. Many species hunt at night and roost during the day. To find owls, search the ground for regurgitated pellets of fur and bone below a nest or roost. Also listen for flocks of small songbirds noisily mobbing a roosting owl. Species: Tytonidae, 19 World, 1 N.A. [North America]; Strigidae, 194 World, 23 N.A.

When you’re training your young naturalists, teach them to ask and answer from their bird guide some of the first questions any naturalist would ask about a new group — about the Barn Owls, for example. How many species? (19 worldwide.) Are there any near us? (Only one species in North America, and the guide’s map will give us more information about its range.) What are their distinctive features? (Mostly nocturnal, large heads with forward-facing eyes, fluffy plumage, cough up pellets that can be found under roosts, and so on.)

Pick a representative species or two to look at in detail each week and read the entry aloud, or have your students study it and then narrate it back to you, explaining all the information it contains. This week, for the Barn Owl family, why not investigate (naturally enough) the Barn Owl (page 294). (There’s only one species in North America, so no extra adjective is usually added to its name.)

All sorts of biological information is packed into the brief species descriptions in your bird guide — can your students tease it out? How big is the Barn Owl? (16 inches long.) What is its scientific name? (Tyto alba.) [The Macaulay Library images now use a revised name, Tyto furcata.] Will you be able to find this species where you live? At what times of year and in what habitat? (Study the range map and range description carefully to answer those questions, and see the book’s back flap for a map key.) Do the males and females look alike? The adults and juveniles? What song or call does this species make? How can you distinguish it from similar species? (The text and illustrations should answer all these questions.)

Barn Owls occur across most of the United States except for the top tier, but they are not particularly common, and because they are almost wholly nocturnal they are not often seen. Their numbers have declined in recent years, possibly because of a decline in small-scale agriculture, which provided the varied hunting and nesting habitats they preferred.

In the “Typical Owl” family — so called just to distinguish them from the Barn Owls — why not take a look at the most widespread and familiar North American owl, the Great Horned Owl (page 294). The bird’s “horns” are of course just paired feather tufts, not bony horns as in mammals. And although Great Horned Owls are found across the entire continent, because they are nocturnal they are more often heard hooting in the dark than they are seen in the daylight.

You can do little ten-minute lessons of this kind with any of the species in your bird guide that catch your interest. Pick one that lives near you, or that looks striking, or that has a strange name, and explore. For example, take a look at the far-northern Snowy Owl (page 296), one of the few owl species that is largely diurnal; or the tiny Elf Owl of the desert southwest (page 298), which is about the size of a soda can; and so on with as many species as you wish.

In all these Friday Bird Families lessons, our aim is not to present a specific set of facts to memorize. We hope instead to provide examples and starting points that you and your students can branch away from in many different directions. We also hope to show how you can help your students develop the kind of careful skills in reading, observation, and interpretation that they will need in all their future academic work.

What ornithological observations and naturalistical notes have you and your students been making in your homeschool this Orion Term? 😊

❡ Homeschool birds: We think bird study is one of the best subjects you can take up in a homeschool environment. It’s suitable for all ages, it can be solitary or social, it can be as elementary or as advanced as you wish, and birds can be found just about anywhere at any season of the year. Why not track your own homeschool bird observations using the free eBird website sponsored by Cornell University. It’s a great way to learn more about what’s in your local area and about how bird populations change from season to season. 🦅

❡ Feed the birds: Setting up a bird feeder is one of the easiest educational activities you can do in a homeschool environment. Here are some tips that will help you get started today! 🐦

❡ Enchiridion: The front matter in your bird guide (pages 6–13) explains a little bit about basic bird biology and about some of the technical terminology used throughout the book — why not have your students study it as a special project. Have them note particularly the diagrams showing the parts of a bird (pages 10–11) so they’ll be able to tell primaries from secondaries and flanks from lores. 🦉

❡ Words for birds: You may not think of your homeschool dictionary as a nature reference, but a comprehensive dictionary will define and explain many of the standard scientific terms you will encounter in biology and natural history, although it will not generally contain the proper names of species or other taxonomic groups that aren’t part of ordinary English. (In other words, you'll find “flamingo” but not Phoenicopterus, the flamingo genus.) One of the most important things students should be taught to look for in the dictionary is the information on word origins: knowing the roots of scientific terms makes it much easier to understand them and remember their meaning. 📖

❡ Come, here's the map: Natural history and geography are deeply interconnected. One of the first questions you should teach your students to ask about any kind of animal or plant is, “What is its range? Where (in the world) does it occur?” Our recommended homeschool reference library includes an excellent world atlas that will help your students appreciate many aspects of biogeography, the science of the geographical distribution of living things. 🌎

❡ Nature notes: This is one of our regular Friday Bird Families posts for homeschool naturalists. Print your own copy of our River Houses Calendar of American Birds and follow along with us! You can also add your name to our free weekly mailing list to get great homeschool teaching ideas delivered right to your mailbox all through the year. 🐦 🦉 🦆 🦃 🦅

❡ Homeschool calendars: We have a whole collection of free, printable, educational homeschool calendars and planners available on our main River Houses calendar page. They will help you create a light and easy structure for your homeschool year. Give them a try today! 🗓

❡ Support our work: If you enjoy our educational materials, please support us by starting your regular Amazon shopping from our very own homeschool teaching supplies page. When you click through from our page, any purchase you make earns us a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thank you for helping us to keep going and growing! 🛒

❡ Join us! The aim of the River Houses project is to create a network of friendly local homeschool support groups — local chapters that we call “Houses.” Our first at-large chapter, Headwaters House, is now forming and is open to homeschoolers everywhere. Find out how to become one of our founding members on the Headwaters House membership page. 🏡