![[Butterfly]](https://riverhouses.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/emoji-butterfly-150x150.png) Our River Houses Poetry Calendar brings together fifty literary friends we’ll be getting to know over the course of the homeschool year, and we invite you and your students to join us! Our poem for this third week of September — for mowing season, the Monarch butterfly migration, and our common labor — is Robert Frost’s “The Tuft of Flowers.”

Our River Houses Poetry Calendar brings together fifty literary friends we’ll be getting to know over the course of the homeschool year, and we invite you and your students to join us! Our poem for this third week of September — for mowing season, the Monarch butterfly migration, and our common labor — is Robert Frost’s “The Tuft of Flowers.”

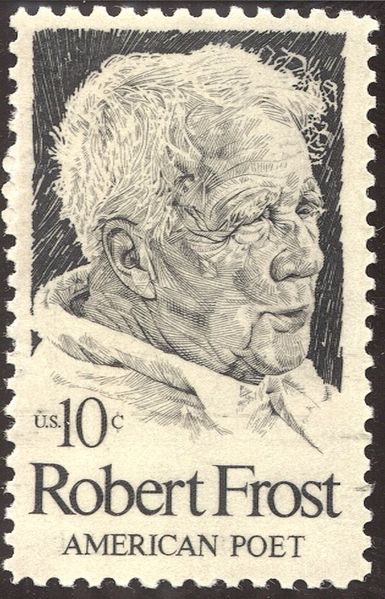

Frost is a wonderful poet for younger people because many of his poems have a regular structure and use direct language. “The Tuft of Flowers” is a narrative poem about mowing a hayfield, and its characters are two farmhands and a butterfly. The first farmhand is the speaker (the narrator); the second farmhand is “off stage” and never appears, although we learn something about him by seeing the work he has done; and the butterfly — the butterfly is the non-speaking character that brings the two farmhands together.

The Tuft of Flowers

I went to turn the grass once after one

Who mowed it in the dew before the sun.The dew was gone that made his blade so keen

Before I came to view the levelled scene.I looked for him behind an isle of trees;

I listened for his whetstone on the breeze.But he had gone his way, the grass all mown,

And I must be, as he had been, — alone,“As all must be,” I said within my heart,

“Whether they work together or apart.”But as I said it, swift there passed me by

On noiseless wing a ’wildered butterfly,Seeking with memories grown dim o’er night

Some resting flower of yesterday’s delight.And once I marked his flight go round and round,

As where some flower lay withering on the ground.And then he flew as far as eye could see,

And then on tremulous wing came back to me.I thought of questions that have no reply,

And would have turned to toss the grass to dry;But he turned first, and led my eye to look

At a tall tuft of flowers beside a brook,A leaping tongue of bloom the scythe had spared

Beside a reedy brook the scythe had bared.I left my place to know them by their name,

Finding them butterfly weed when I came.The mower in the dew had loved them thus,

By leaving them to flourish, not for us,Nor yet to draw one thought of ours to him,

But from sheer morning gladness at the brim.The butterfly and I had lit upon,

Nevertheless, a message from the dawn,That made me hear the wakening birds around,

And hear his long scythe whispering to the ground,And feel a spirit kindred to my own;

So that henceforth I worked no more alone;But glad with him, I worked as with his aid,

And weary, sought at noon with him the shade;And dreaming, as it were, held brotherly speech

With one whose thought I had not hoped to reach.“Men work together,” I told him from the heart,

“Whether they work together or apart.”

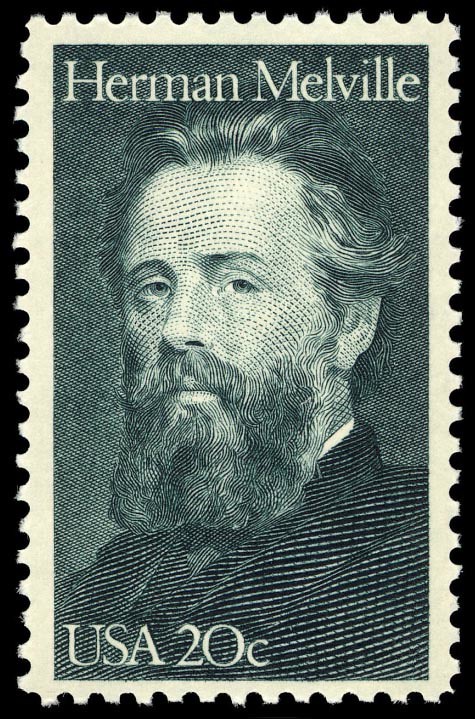

Robert Frost (1874–1963) was one of the most popular American poets of the twentieth century and every homeschool student should recognize his name. Frost’s poems are often built around a set of careful observations of the natural environment, and his details are always precise. Have your students ever watched someone mow a field with a scythe? The video below illustrates the process very well. The man in this scene is performing the first step, which the poem’s “off-stage” character performed at dawn before the narrator arrived: he is cutting the grass and leaving it in rows. Either he or someone else will come back later to turn the rows over so the cut grass will dry and not rot.

“I listened for his whetstone on the breeze,” says Frost. Skip ahead in the video to the 2:25 mark and you’ll hear exactly what that sounded like (along with some “wakening birds around”).

“I left my place to know them [the flowers] by their name, / Finding them butterfly weed when I came.” Is “butterfly weed” an imaginary invention? Not at all. Asclepias tuberosa (butterfly weed) is a common field-flower of the northeastern United States that is particularly attractive to butterflies.

![[Butterfly Weed]](https://riverhouses.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/butterfly-weed.jpg)

One reason Frost’s poems are especially good for teachers is that they often provide clear and simple examples of specific literary techniques and structures, examples that you can share with your students. “The Tuft of Flowers,” for instance, is an entire poem composed of couplets — rhymed pairs. That’s a basic term every beginning literature student should know:

A leaping tongue of bloom the scythe had spared

Beside a reedy brook the scythe had bared.

Entire poems in couplets are not too common in English; more often couplets are used at the conclusion of a poem or a scene in a verse play as a kind of poetical period. Shakespeare often ends his scenes with couplets, as he does just before the Battle of Agincourt in Henry V:

Now, soldiers, march away,

And how Thou pleasest, God, dispose the day.

It’s mid-September, and summer is grading into autumn. In many parts of the United States the Monarch butterfly migration is underway — I’ve seen several in the last few days in my neighborhood. Perhaps you can find a few Monarchs in an open field near you this week and trace the paths they take on tremulous wing. Who knows where they may lead you. 🦋

What wonderful words and poetical productions will you and your students be examining in your homeschool this Cygnus Term? 😊

❡ This is a printable lesson: Down at the bottom of this post you’ll find a custom “Print” button that will let you create a neat and easy-to-read copy of this little lesson, and it will even let you resize or delete elements that you may not want or need (such as images or footnotes). Give it a try today! 🖨

❡ Making a new friend: When you introduce your students to a new poem, especially one in a traditional form, take your time, and don’t worry about “getting” everything right away. A good poem is a friend for life, and as with any friend, it takes several meetings to get acquainted. Before you even start to think about meaning, take a look at the poem’s structure. How many lines does it have? Are the lines grouped into stanzas? How many lines in each stanza? How many syllables in each line? Many traditional poems are highly structured and fit together in an almost mathematical way, which you can discover by counting. Do the lines rhyme? What is the rhyme scheme (ABAB, AABA, ABCD, or something else)? By uncovering these details of structure your students will come to appreciate good poems as carefully crafted pieces of literary labor. 📖

❡ Whether they work together or apart: If a special line or turn of phrase happens to strike you in one of our weekly poems, just copy it onto your homeschool bulletin board for a few days and invite your students to speak it aloud — that’s all it takes to begin a new poetical friendship and learn a few lovely words that will stay with you for life. 🦋

❡ Looking in the lexicon: There’s some wonderful vocabulary in this week’s poem to look up in your family dictionary: whetstone, tremulous, scythe, [be]wildered. Send your students to the dictionary also for any poetical terminology they encounter: stanza, couplet, quatrain, sonnet, pentameter, hexameter, iambic, dactylic, and more — wonderful words, every one! 🔍

❡ Literary lives: The website of the Poetry Foundation includes biographical notes and examples of the work of many important poets (including Robert Frost) that are suitable for high school students and homeschool teachers. ✒️

❡ Here, said the year: This post is one of our regular homeschool poems-of-the-week. Print your own River Houses Poetry Calendar to follow along with us as we visit fifty of our favorite friends over the course of the year, and add your name to our River Houses mailing list to get posts like these delivered right to your mailbox every week. 📫

❡ Homeschool calendars: We have a whole collection of free, printable, educational homeschool calendars and planners available on our main River Houses calendar page. They will help you create a light and easy structure for your homeschool year. Give them a try today! 🗓

❡ Support our work: If you enjoy our educational materials, please support us by starting your regular Amazon shopping from our very own homeschool teaching supplies page. When you click through from our page, any purchase you make earns us a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thank you for helping us to keep going and growing! 🛒

❡ Join us! The aim of the River Houses project is to create a network of friendly local homeschool support groups — local chapters that we call “Houses.” Our first at-large chapter, Headwaters House, is now forming and is open to homeschoolers everywhere. Find out how to become one of our founding members on the Headwaters House membership page. 🏡